Exhaust Flame Safety Checker

Assess Your Exhaust Flame Safety

Answer the following questions about your exhaust flame to determine its safety level and recommended actions.

Safety Assessment Result

Quick Takeaways

- Exhaust flames are usually caused by a rich fuel mix, misfires, or aftermarket exhausts.

- They can damage the catalytic converter, pose a fire risk, and may be illegal on public roads.

- Regular diagnostics and proper tuning keep flames under control.

- Using a flame‑suppressor or “quiet‑tip” can reduce visible flames without sacrificing power.

- Know your local road‑safety laws - in Australia, uncontrolled exhaust flames can attract fines.

Are exhaust flames safe? The short answer is: they’re rarely "safe" in the sense of being harmless, but they’re often harmless if you know why they happen and keep them in check. Below we break down what produces those fireworks, the real risks involved, and what you can do to stay both fast and compliant.

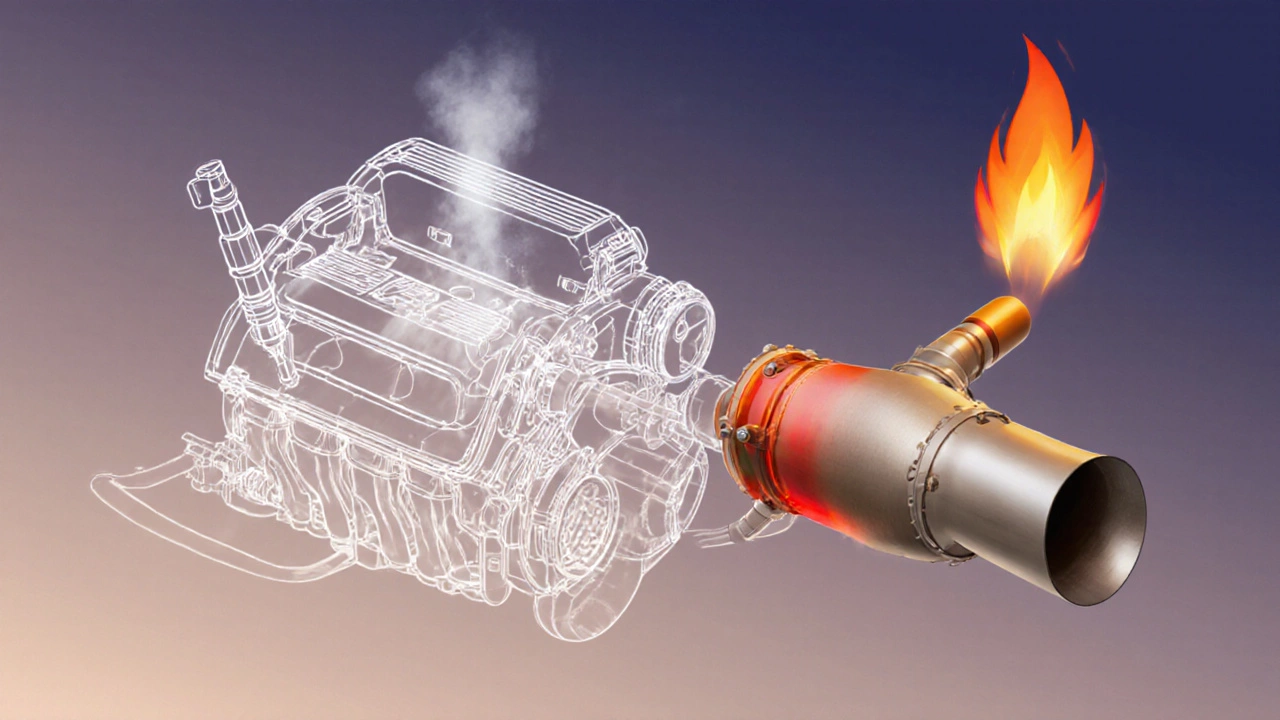

What exactly is an exhaust flame?

When a vehicle’s engine burns more fuel than the air can handle, unburnt hydrocarbons exit the combustion chamber and ignite in the hot tailpipe. This creates a brief flash that shoots out of the exhaust. In technical terms, an exhaust flame is a momentary ignition of unburned fuel in the exhaust system, visible as a fire plume from the tailpipe. It’s a symptom, not a feature, and its safety depends on the underlying cause.

Why do exhaust flames appear? Common causes

Understanding the root causes helps you decide whether the flame is a harmless showpiece or a warning sign. The most frequent culprits are:

- Rich fuel mixture - When the engine receives too much fuel relative to air (high air‑fuel ratio), excess fuel can ignite downstream.

- Engine misfire - A misfiring cylinder ejects unburned mixture that ignites later in the exhaust.

- Turbo lag or boost pressure - Sudden pressure changes can push unburned fuel into the hot turbine housing.

- Aftermarket performance exhaust - Less restrictive pipes lower back‑pressure and raise exhaust temperature, making ignition more likely.

- Faulty oxygen sensor - Bad sensor data leads the engine control unit (ECU) to run richer than needed.

- Cold start in cold weather - A cold catalytic converter doesn’t fully oxidize fuel, allowing combustion in the pipe.

Each cause ties back to a component of the exhaust system the network of pipes, mufflers, and catalytic converters that directs gases away from the engine or its fuel‑delivery side. Let’s look at the key parts involved.

Key components linked to flame formation

- Catalytic converter a heat‑treated ceramic device that reduces harmful emissions by oxidizing gases - When it’s cold or failing, it can’t fully burn fuel.

- Fuel injector a precision valve that sprays fuel into the combustion chamber - Leaking or stuck injectors cause rich spots.

- Oxygen sensor monitors exhaust oxygen levels to help the ECU balance fuel - Bad readings skew the mix.

- Engine misfire a failure of a cylinder to fire properly, leaving unburned fuel - Often traced to spark plugs, coils, or compression issues.

- Aftermarket performance exhaust a less restrictive pipe designed for higher flow and sound - Increases temperature and reduces back‑pressure.

- Air‑fuel mixture the ratio of air to fuel entering the engine, typically around 14.7:1 for gasoline - Too rich = more leftover fuel.

Safety risks: When flames become dangerous

Not every flash is a deal‑breaker, but several hazards can arise if you ignore the warning signs.

| Cause | Potential Damage | Safety Rating |

|---|---|---|

| Rich mixture (minor) | Increased fuel consumption, carbon buildup | Low |

| Engine misfire (moderate) | Exhaust heat spikes, catalytic converter overheating | Medium |

| Cold catalytic converter (high) | Possible fire in the tailpipe, damage to heat‑shield | High |

| Aftermarket exhaust with no flame‑suppressor (variable) | Legal violation, public safety hazard | Medium‑High |

Key hazards include:

- Fire danger - If the flame contacts the under‑tray, fuel‑laden components, or dry vegetation, it can start a vehicle fire.

- Catalytic converter damage - Repeated overheating can melt the ceramic honeycomb, leading to costly replacement.

- Excessive carbon deposits - They choke the exhaust, reduce performance, and may clog the O₂ sensor.

- Legal penalties - In Queensland and other Australian states, uncontrolled exhaust flames can be deemed a public nuisance, attracting fines or vehicle inspection failures.

- Personal injury - Burn risk to passengers or by‑standers, especially when loading/unloading the car.

How to tell if your exhaust flames are safe (or not)

Before you start swapping parts, perform a quick visual and sensory check.

- Observe the flame length. A brief spark (1‑2 inches) that disappears quickly is usually a symptom of a rich run‑off. A tall, sustained plume (5+ inches) signals higher risk.

- Smell the exhaust. A sweet, unburned fuel odor points to a rich mixture; a metallic or burnt‑rubber scent may indicate overheating components.

- Feel for heat. After a short drive, gently touch the rear‑center of the exhaust pipe (use a cloth). If it’s scorching hot (<200°C) it’s normal; if it’s dangerously hot (>300°C) you may have a failing catalytic converter.

- Check for soot buildup inside the tailpipe or on the inside of the muffler. Excessive black residue means incomplete combustion.

- Run a diagnostic scan. Modern OBD‑II tools will flag misfire codes (P0300‑P0306) or O₂ sensor failures (P0130‑P0135).

If you notice any of the red‑flag symptoms-long flames, odd smells, extreme heat, or diagnostic trouble codes-treat the issue as unsafe.

Preventing and taming exhaust flames

Here’s a practical checklist you can follow after diagnosing the root cause.

- Retune the ECU - Adjust the fuel map to lean out the mixture, especially when using a larger exhaust.

- Replace faulty injectors or O₂ sensors - New components restore accurate fuel‑air balance.

- Upgrade spark plugs and ignition coils - Stronger sparks reduce misfires.

- Install a flame‑suppressor tip - Also called a “quiet tip” or “catalytic tip”. It cools the gases enough to extinguish visible flames while keeping flow fairly unrestricted.

- Warm up the catalytic converter - Short idle periods before hard acceleration give the converter time to reach operating temperature.

- Use high‑quality fuel - Lower ethanol blends (e.g., E10) burn cleaner, reducing excess hydrocarbons.

Remember, the goal isn’t to eliminate every spark-some performance setups intentionally allow a brief flash for show-but to keep it within safe, legal boundaries.

Legal perspective in Australia

Australian road‑traffic legislation treats uncontrolled exhaust flames as a potential hazard. In Queensland, the Transport Accident Act classifies a “visible flame from a vehicle exhaust” as a breach of the safety standards for motor vehicles, which can result in a fine of up to $400. Similar rules exist in New South Wales and Victoria under their respective Vehicle Standards Acts.

Beyond fines, an inspection failure can prevent registration renewal, effectively grounding the car until the issue is resolved. For touring and track days, many clubs require participants to use "flame‑dead” exhaust tips to protect spectators.

In short: if you’re driving on public roads, keep flames short (under 2‑3 inches) and avoid any situation where the flame could reach pedestrians or vegetation.

Bottom line: are exhaust flames safe?

They’re not "safe" by definition because they signal that something in the combustion or exhaust process is off‑balance. However, with proper tuning, regular maintenance, and sensible hardware choices, the flashes can be kept mild enough to avoid damage, stay legal, and still give you that adrenaline‑pumping visual cue.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do my turbocharged cars show bigger flames than naturally aspirated ones?

Turbochargers compress intake air, raising combustion temperatures. When the turbo spools up, a sudden surge of pressure can push unburned fuel into the hot exhaust, creating larger, more visible flames. Proper boost control and richer fueling during spool‑up can mitigate this, but a short flame is common in tuned turbos.

Can I legally install a flame‑suppressor tip on my performance exhaust?

Yes. Flame‑suppressor (or "quiet") tips are designed to meet road‑legal emission standards while reducing visible flames. As long as the tip is certified for use on public roads in your state, it keeps you within the law.

Do exhaust flames affect fuel economy?

Yes, albeit modestly. A consistently rich mixture that causes flames also burns more fuel per mile. Fixing the underlying issue-leaner tuning, proper sensor operation-will usually improve economy by 2‑5%.

My car’s exhaust flame made a loud pop. Is that a sign of damage?

A loud pop indicates a sudden ignition of a larger fuel charge, which can create a pressure wave that stresses the exhaust pipe and muffler. Repeated pops may crack the pipe or loosen mounting brackets. It’s wise to have the exhaust inspected after a pop.

Will a cold‑weather start always cause exhaust flames?

Cold starts often produce brief flames because the catalytic converter hasn’t reached its operating temperature. A short idle for 30‑60 seconds before aggressive driving usually eliminates the problem. Persistent flames after the converter is hot suggest a deeper issue.

By staying vigilant, running regular diagnostics, and choosing the right hardware, you can keep those tailpipe fireworks under control, protect your car’s internals, and stay on the right side of the law.